Archive for the ‘Parliament’ Category

May Day has traditionally been a time of protests, marches and demonstrations.

You can go right back to 1517 and the time of the Tudors, when a mob of young apprentices rampaged through London targeting the businesses of foreign merchants.

But the origin of our present May Day holiday lies in the fight for an eight-hour working day, which began across the Atlantic when the American Federation of Labor took industrial action on 1 May 1886. A bomb was thrown in Chicago killing a policeman and there was a huge international outcry when eight anarchists were falsely accused of the crime and seven were sentenced to death. The police who had earlier shot dead two strikers were accused of fabricating evidence and socialists all over the world, including local groups like the Peckham Reform Club, spoke out against the trial and sentences.

The movement for a shorter working day did not die with those who became known as the Chicago Martyrs. The American Federation of Labor called for a national day of demonstrations and strikes on 1 May 1890, which was echoed by the International Socialist Conference in Paris. As a result, demonstrations went ahead all over the United States and Europe, which is why May Day became an international festival of working class solidarity.

In London, there was a huge demonstration in Hyde Park, with many local workers setting off from Camberwell Green. The procession was headed by the North Camberwell Radical Club’s band who called for ‘Eight hours’ work, eight hours’ pay, eight hours’ rest for eight bob a day’.

Initially, May Day was intended to be a one-off protest. But it continued largely because of the flourishing trade union movement at the time and as a result the size of the London marches grew larger every year. In 1892 a huge crowd estimated at half a million walked from Westminster Bridge to Hyde Park, led by the dock workers of Bermondsey.

It was during this time that elements from traditional May Day celebrations began to be incorporated into socialist demonstrations. Artists and writers like Walter Crane, whose work can be found in the South London Gallery in Peckham, and William Morris started combining socialist values with the familiar ‘Merrie England’ imagery of May queens, garlands and angels. Morris used images of mediaeval pageantry and a lost rural idyll to criticise the squalor of industrial capitalism, while the artist Walter Crane drew a workers’ maypole, with socialist slogans like ‘Solidarity’ and ‘Leisure for All’ written on the ribbons.

This tribute to the workers of the world, called on labourers and factory workers to come forth on May Day and “be glad in the sun” But for most workers relaxing in the green fields on a working day was not an option, it was only the reduction of working hours and the extension of the weekend and holidays that could make that possible, so the marchers sang songs that contrasted the mirth of May Day festivities with the tough and weary world of work.

In 1926, May Day marked the start of the General Strike, and there were many clashes here at the Elephant and Castle. The strikers would stop buses, lorries and vans that didn’t have a TUC permit, but this didn’t deter many blackleggers from trying to force their way through, which led to violence and two buses being set on fire. As a result, the police constantly patrolled the Elephant, many on horseback, and kept chasing people away by riding at them and swinging their truncheons.

There were more local clashes with police in the 1949 when the government tried unsuccessfully to ban May Day marches, but by the sixties these events were beginning to dwindle and when it became a Bank holiday in 1978, it’s radical past seemed to be fast disappearing. So a number of activists launched their own alternative events to take May Day back to its roots, including John Lawrence, who lived in Camberwell, and began organising marches in the 70s that ended in a park with free music, dancing and sport.

By the year 2000 May Day had returned as a more militant protest, due to a broad coalition of activists under the anti-capitalist banner. Green issues had also become more prominent and protestors made the headlines by raising a Maypole next to Parliament, planting flowers in Parliament Square and giving the statue of Winston Churchill a turf Mohican.

The following year a large crowd met at Elephant and Castle for an anti-privatisation picnic before marching on to the West End, where militant anarchists ruined the party atmosphere by breaking away from peaceful demonstrators and smashing shop windows in Tottenham Court Road.

Since then there have been a number of small peaceful radical May Day events that have been a big success, without hitting the headlines. In 2007, a procession made its way from Camberwell to Kennington Park, where the Chartists, a working class movement for political reform, demonstrated in 1848. After reaching the park, the marchers gathered for a picnic and danced around a workers’ maypole, with an imitation surveillance camera on top. Protests like this prove that May Day is not simply backward looking, but remains an ever-changing event that still offers workers a unique opportunity to join together, march for their rights and demonstrate against injustice.

If you walk along the riverside in Bermondsey you will come to a great little pub called The Angel, where for many years a statue of the great reforming MP Dr Alfred Salter sat waving on a bench.

Sadly the statue was taken in 2011, probably for the value of its bronze, but local memories of Dr Salter and his wife remain as strong as ever in the borough and there is now a fundraising campaign to erect a new statue outside the Angel, which has been supported by Southwark Council.

Alfred Salter was born in Greenwich in 1873 and had a brilliant career as a medical student at Guy’s hospital, but it was Bermondsey where he made his home. He spent his working life, first as a GP and then later as an MP, trying to improve the lot of the Bermondsey people, many of whom lived in overcrowded insanitary housing, that led to poor health.

Alfred was doctor to thousands of patients in an area where there was a case of TB in every third house and where illness claimed hundreds of children each year. There he campaigned for, and achieved, the tubercular-testing of milk.

A prestigious career was in prospect, but Alfred decided to become a local GP at the Bermondsey Methodist Settlement and dedicate his life to fighting the appalling poverty and disease that was rife in the local slums. The Settlement had been created by John Scott Lidgett who had a vision of the settlement as a “community of social workers who come to a poor neighbourhood to assist by methods of friendship and cooperation those who are concerned with upholding all that is essential to the well-being of the neighbourhood”.

Alfred was a doctor to thousands of patients in an area where there was a case of TB in every third house and where illness claimed hundreds of children each year. As a result, he campaigned for, and achieved, the tubercular-testing of milk and established mutual health insurance schemes.

While working at the Bermondsey Settlement he met and fell in love with Ada Brown, the leader of the Mothers’ Meeting and the Girls’ Club. Ada shared his political and social views. He converted her to socialism and she encouraged him to become a Christian. They joined the Peckham branch of the Society of Friends together, and decided to devote their lives to helping the people of Bermondsey.

In 1900, the year of their marriage, he established a general medical practice in the area and the couple worked together in trying to alleviate the effects of poverty in the largely working class area. Alfred rented out a shop on the corner of Jamaica Road and Keeton’s Road and turned it into a surgery. He upset his professional colleagues by charging only sixpence for medical conultations and chose to offer services free to those who could not pay. This work was to lead to the establishment of a pioneering comprehensive community health centre, 20 years before the NHS was founded.

Alfred’s takings during the first week amounted to 12s. 6d. This did not last long, however. Within a few weeks his problem became too many clients. It was not only his low charges which attracted patients, it was the treatment he gave and he was so successful he soon needed to recruit four other doctors to the surgery. Alfred ran the surgery as a local cooperative and the five doctors shared their takings equally.

His daughter Joyce was born in June 1902 and he was elected to Bermondsey Borough Council as a Liberal Whip and a JP, but he and his wife gradually grew disillusioned with the Liberal Party’s lack of radicalism and joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP).

At this point the Salter’s old only child, Joyce, who was known in Bermondsey as “our ray of sunshine” caught scarlet fever and died aged eight in June 1910. This personal tragedy might have been averted had Joyce been educated elsewhere, which increased their commitment to the area and its people.

In the 1922 General Election, Alfred was elected to represent Bermondsey West, deciding that by entering politics he could bring about social change quicker and more effectively. Through his efforts play facilities were established at Long Lane, Tooley Street and Tanner Street. He prepared plans to replace tenements with lower density developments, such as Wilson Grove, which can still be seen today. Alfred successfully campaigned for a solarium to treat people with TB and children were sent to recuperate in Switzerland.

His wife Ada became the first woman Labour councillor in London and the first woman Labour mayor in the British Isles. All the couple’s political and social activities were undertaken to try to improve the life of their community. Their aim was to create better housing and proper water supplies in tenement blocks, school meals for children, the establishment of parks and the purchase of a convalescent home for Bermondsey people. They built the first public baths, swimming pools and special baths for babies, and were said to be “among the greatest personal contributors to social progress this century”.

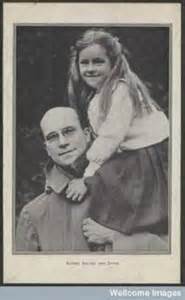

He is still held in great esteem in this borough, and this was shown when Alfred’s statue was erected on a bench outside the Angel. Diane Gorvin’s statue showed Alfred waving to Joyce, who was leaning against the Thames wall with her cat nearby. It represented a daydream of the old doctor remembering happier times when Joyce was still alive.

When the statue was stolen a reward of £1,000 was offered, but sadly no one returned it. A group of local residents therefore set up a fundraising campaign to replace it and a statue of Ada to join him and Joyce. The target is £100,000, which will pay for the statues plus additional security including CCTV and electronic sensors. About £16,000 has been raised so far, which Southwark council has promised to match. The statue of Joyce and the cat were removed after the theft and are being kept in storage for the time being.

There are a number of other local memorials to the Salters, including a plaque at Bermondsey tube station and the Ada Salter Garden in Southwark Park. But the most famous one was a statue of Dr Salter and his daughter Joyce, which was stolen a couple of years ago. Local residents were so upset they have set up a fundraising charity to replace it and create a new one. The target is £100,00 and the charity has so far raised over £16,000. Southwark council has pledged to match the amount raised, which means they now have over £32,000 and so are a third of their way to the target figure.

Tim Russell